“Nay, Traveller! Rest.”: On Tourism and Literature

In the spring of 2019, when life was much simpler without global pandemics and whatnot, I was trying to decide where I wanted to spend my annual leave that summer (a struggle not present this year). As I had been reading about the romantic movement in England, the Lake District came to mind. After a bit of googling around I was sold. The fells, the valleys, the lakes, (the sheep) … Even better, the national park was reachable by public transport! I learned that the area had been a tourist hotspot for hundreds of years, a fact that I will explore a little further later in this article.

Authors for centuries have told their stories set in glorious landscapes, creating vivid pictures with only words as their paint, letting us experience the same that they may have felt that rainy night by the lake or that tranquil spring morning in the valley. Described as the ‘quintessential Lake District poem’ by the national park’s website, William Wordsworth’s poem Daffodils (1807) enamours the reader. Here I have included the first stanza of the poem:

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

June 29, I arrive to Keswick. I am going to climb up Cat Bells, one of the most popular fells in the Lake District. Crossing Derwentwater, the boat is full of people, as was the one that left before. I can’t help but wonder, how the Lake District became the tourist attraction that it is?

In the 18th century, England experienced a rise in domestic tourism due to the difficult political situation which led to a decrease in international travel. Another important factor was urbanisation: having very little living space had its drawbacks, and though public parks were already recognised as an essential part of urban planning, the polluted cities didn’t have much to offer for peace of mind.

Travel guides and educational board games also played a part in birth of tourism in Britain. Educational board games were mainly designated to teach geography to children, but they also promoted tourist destinations. Interestingly, despite its popularity among writers the Lake District rarely was a destination to visit in the board games.

Early tourism in Lake District was fuelled by Thomas West’s A Guide to the Lakes (1788). William Wordsworth, the most well-known member of the group of so-called ‘Lake Poets’, published his guide to the Lake District titled A Guide through the District of the Lakes in 1810. It was not the first or only publication to promote the beauty of the lakes, valleys and fells of the area, but it surely was among the most influential ones in terms of nineteenth-century tourism. Author and illustrator Alfred Wainwright is famous for his detailed guidebooks to the Lake District, of which the first was published in 1955. The following extract is from the final page of The Western Fells (1966).

The fleeting hour of life of those who love the hills is quickly spent, but the hills are eternal. Always there will be the lonely ridge, the dancing beck, the silent forest; always there will be the exhilaration of the summits. These are for the seeking, and those who seek and find while there is still time will be blessed both in mind and body.

As important as they were, travel guides were not the only form of literature that inspired people to explore new places. Romantic poetry often drew its power from nature, and in some cases the places where the poems had originated were mentioned directly. In Wordsworth’s poem Lines Left Upon A Seat In A Yew-Tree, the yew-tree in question is known to have been by Esthwaite Water:

Nay, Traveller! rest. This lonely Yew-tree stands

Far from all human dwelling: what if here

No sparkling rivulet spread the verdant herb?

What if the bee love not these barren boughs?

Yet, if the wind breathe soft, the curling waves,

That break against the shore, shall lull thy mind

By one soft impulse saved from vacancy.

Like people are visiting movie locations today, literature has also motivated people to visit places they have read about, and its history goes much beyond Romantic era.

It is good to keep in mind that domestic tourism was mostly the pastime of middle and upper classes and arguably, it still is. Today, if you are not picky, even travelling abroad is cheap. Still, there are plenty of people that don’t travel: Eurostat figures from 2016 show that approximately 64 percent of the UK residents took at least one overnight trip that year. That leaves us with one third that didn’t travel. The result is close to EU average. There are many factors why people don’t travel. For a first timer, booking flights, train tickets and hotel rooms may be overwhelming. Not everyone has paid annual holidays (freelancers, for one). And while travelling for twenty-somethings with no kids may be relatively cheap, the situation is different when you are travelling as a family. Of course, the gap between the people that have the opportunity and those that do not is considerably smaller, and the former group is relatively larger. Then again, not everyone wants to travel.

In contemporary discussion, a topic that often comes up in relation to tourism is sustainability. The first steps of British environmental movement were taken in the late 1800’s in the form of such groups as National Trust. Beatrix Potter, the author known for her children’s books, Peter Rabbit in particular, was a dedicated conservationist. She donated all her property to National Trust: that way everyone could enjoy the beautiful landscape much adored by Potter.

Nature preservation was one of the great themes of Britain’s post-war reconstruction. The ideal first endorsed by Romantic literature and early environmentalists had by now become widely recognised as a great national matter.

One could claim that it couldn't have happened without the impact of these authors. However, the cultural climate had already started to shift towards one that enjoys rather than controls, which eventually led to the birth of modern nature conservation and the founding of national parks in twentieth-century England. It is impossible to say how much of this can be attributed to literature, the Lake Poets for example, but what can be said is that the influence of their poetry is something not to be overlooked.

While writing this article I stumbled upon a Taylor Swift song published in August 2020. The name of the song is ‘The Lakes’ and it goes as follows:

Take me to the lakes, where all the poets went to die/

I don't belong, and my beloved, neither do you/

Those Windermere peaks look like a perfect place to cry

In the 21st century the Lake District continues to spark interest among travellers, both international and domestic. Furthermore, the much-valued Lake Poets have left a standing impact with their descriptions of nature and its grandeur. While the ongoing pandemic restricts us experiencing new wonders first-hand, literature might be the key for new discoveries – or indeed, as in my case, one way to relive good memories – and it is available for those who do not travel for one reason or another as well.

The Lake District National Park was established in 1951, making it the second national park in the UK. With approximately 19 million (2018) annual visitors, the Lake District enjoys great popularity among hikers and other sorts of nature-lovers. The area is known for its astonishing views: All the highest peaks of England are in Lake District. Situated in Cumbria, North West England, it is only a 2-hour train trip away north from Manchester. The Lake District has been a UNESCO Word Heritage Site since 2017.

References

Barnett, David. (2009, August 5). Remembering Beatrix Potter's devotion to the Lake District. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2009/aug/05/beatrix-potter-lake-district

Dove, Jane. (2016). Geographical board game: promoting tourism and travel in Georgian England and Wales. Journal of Tourism History, 8(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1755182X.2016.1140825

Evans, David. (1997). A history of nature conservation in Britain (2nd edition). Routledge.

Sweet, Rosemary. (2016, December 22). Domestic tourism in Great Britain. British Library.https://www.bl.uk/picturing-places/articles/domestic-tourism-in-great-britainParticipation in tourism for personal purposes. (n.d.). Eurostat. Retrieved October 6, 2020, from https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=tour_dem_totot&lang=en

The English Lake District. (n.d.). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved September 29, 2020, from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/422/

Tourism. (n.d.). Lake District National Park. Retrieved September 29, 2020, from https://www.lakedistrict.gov.uk/learning/factstourism

Wainwright, Alfred. (2016). The Western Fells. Frances Lincoln Publishers Ltd.

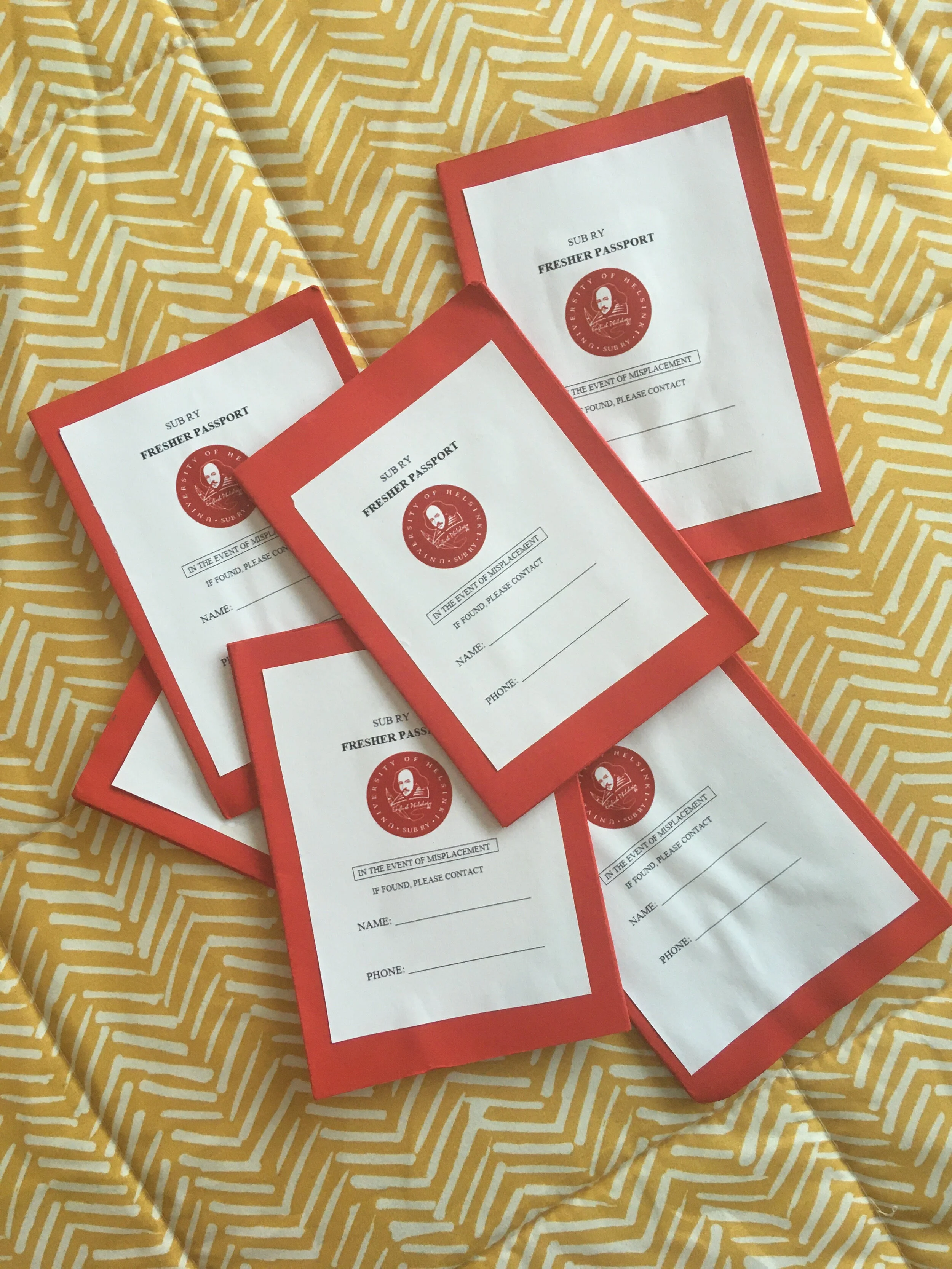

Photo also by Miia E. Hankonen